I’ve attempted to reach Ambae’s summit three times. My first visit coincided with the catastrophic 2017/2018 eruption, when most of the island lay abandoned. Safety concerns forced us to turn back before reaching the top. The second expedition proved more successful – we made it to the summit and witnessed the week-old lava flows and devastated forest. Yet near-whiteout conditions plagued the entire climb, severely hampering our observations. Despite the poor visibility, we became the first people to descend into the second tier of the newly formed cone. Determined to experience the summit in clear weather, I made a promise to return. This year, I finally kept that promise.

The flight from Port Vila to Longana, Ambae’s northern airport, lasted just over an hour in clear conditions. Unlike Ambrym’s nerve-wracking approach, Longana boasts a fully paved, lengthy runway that makes for far smoother landings. My long-time friend William and chief guide Justin were waiting for me. We loaded into a truck and headed straight to the nearest shop to stock up on bottled water.

With favorable weather and limited time, we decided to tackle Manaro Vui that same day – a gamble that would mean a rushed schedule with portions of hiking after dark. The two-hour drive from the airport was a challenge, the route deteriorating into a gauntlet of ruts and mud. During my previous visit, we’d been forced to abandon the vehicle well before reaching the trailhead village. This time, our driver refused to give in. Inevitably, we bogged down in which seems to be a ritual on every expedition. The infrequent visitors mean the road receives virtually no maintenance. Armed with spades, we set to work: excavating trenches, laying fresh scoria across the muddiest sections, and coaxing the truck through the worst stretches.

At the trailhead village, we assembled a team of eight porters, redistributed our equipment across multiple packs, and began the ascent toward the caldera where we’d spend the night. The trail winds through small villages before entering into dense jungle of towering trees and giant ferns. The route is marked by five checkpoints. The forest requires constant vigilance: snakes, scorpions, and massive spiders lurk throughout. Fortunately, the ticks that tormented us on Ambrym were absent here. Local opinion remains divided on whether the snakes are venomous, so we gave them wide berth. The climb proved hot and muggy, but the porters had thankfully agreed to carry all my gear – a relief, given that illness had left me severely drained.

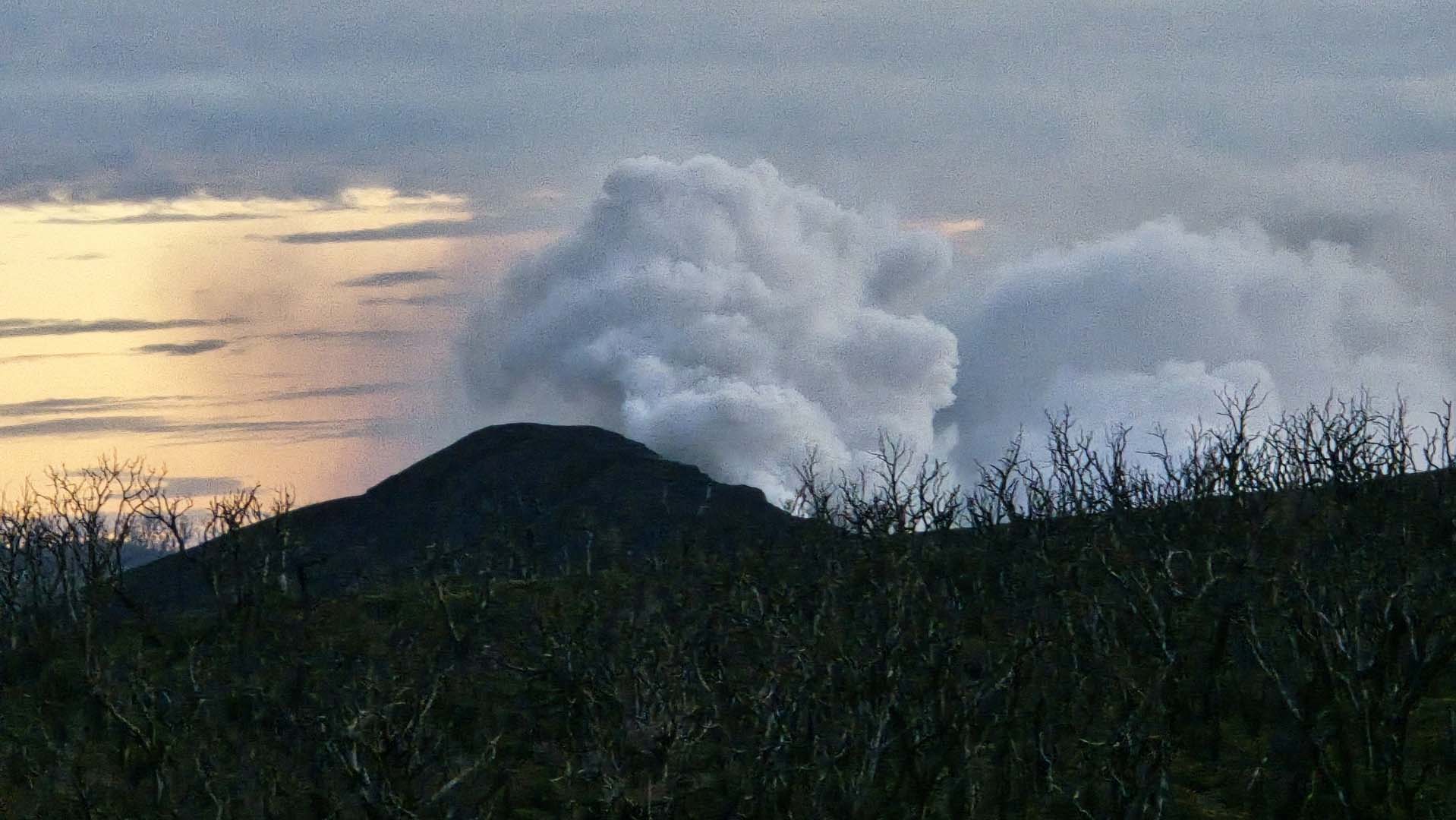

Darkness was gathering as we arrived at the summit. But the conditions were spectacularly clear. Before us rose the newly formed cone, billowing enormous plumes of water vapor and sulphur dioxide, making it one of the world’s most prolific volcanic gas emitters. Our journey wasn’t finished. We still had to descend the caldera wall, ford a stream, and traverse the caldera floor to reach our campsite.

We got our tents up quickly, boiled water, and wolfed down dehydrated meals. The clear conditions allowed me to capture several professional shots, and I noticed an intense glow from the cone – lava was either at the surface or tantalisingly close. Minutes later, fog swallowed everything, reducing visibility to five meters.

I didn’t get much sleep that night. I lay awake, anxious about the weather, dreading a repeat of the whiteout conditions. According to the local guides, fog is virtually permanent here.

When I unzipped my tent the next morning, I could barely believe what I saw: perfect visibility, with patches of blue sky and no wind. I immediately launched the drone, sending it over five kilometers away and capturing spectacular footage.

We packed our day bags and set out toward the active cone. This landscape ranks among Earth’s most otherworldly.

After thirty minutes, we reached the inner tephra ring. Lake Voui (one) shimmered an almost turquoise blue, while the new cone emitted massive clouds of gas and steam in the distance. The 2023 lava flows were clearly visible. We found a spot where we could cautiously descend to the second tier – the same level we’d reached on my previous visit. This time, excellent visibility allowed detailed observations. But I wanted more. I decided to attempt a descent to the crater floor itself – virgin ground where no one had ever stood.

Without proper rigging equipment, it became a precarious free climb and slide. The decision was probably reckless. Any fall or injury would leave me stranded without hope of rescue. After a harrowing descent, I touched down. The sensation of being the first person to walk this ground was surreal.

The surface proved treacherous with a deep layer of loose lapilli that shifted underfoot. I first approached the 2023 lava flow, where I observed beautiful examples of vertical slab inflation. When lava supply remains steady on flat terrain, molten material continues injecting beneath the solidified crust, building internal pressure that lifts the overlying layers. Surrounding these were a’a flows of brittle, fractured clinker.

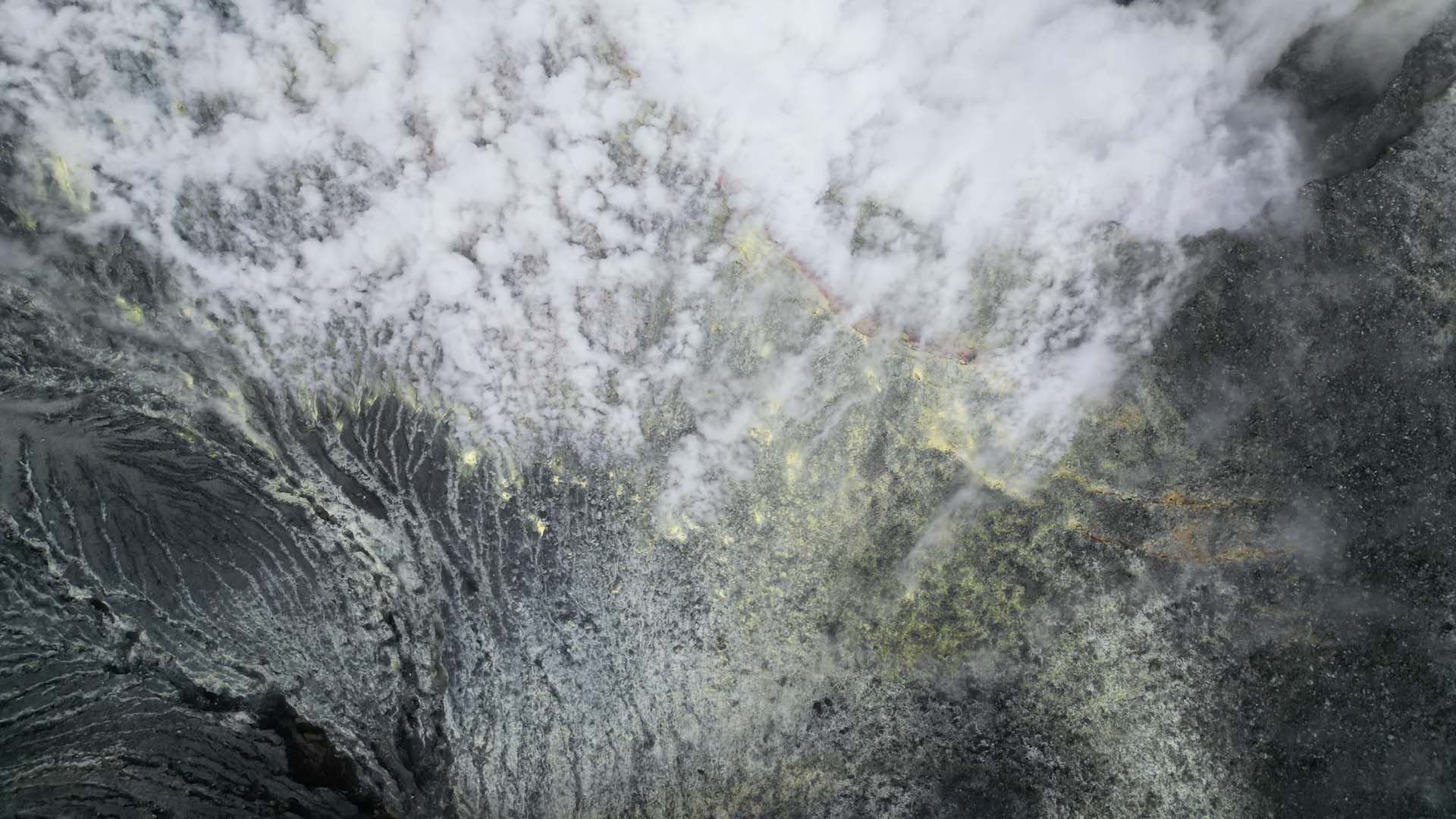

Heading over to the SE section of the crater was a flat plain, covered in sulfur and iron-rich minerals resulting from hydrothermal alteration. The area is littered with hydrothermal vents, surrounded by altered ground coated with sulphur, silica, and iron oxide minerals.

A fumarole chimney formed from the differential erosion.

Still hot lava rock, likely part of an active vent.

Closer to the central crater, the volcanic activity intensified dramatically. I was met with heavy fumarolic gassing, where thick steam and gas plumes billowed from the main active vents. These powerful clouds were mostly water vapour, but they carried an intense concentration of noxious sulphur dioxide and hydrogen sulphide gases.

The striking blue gas pouring from the main vent was remarkable, indicating an exceptionally high concentration of sulphur dioxide being released.

The ground was richly laced with sulfur deposits.

One area that demands close monitoring is a small lava dome we observed in this zone; it was visibly hot. The local guides will be photographing the dome frequently to track its growth patterns and assess the potential hazard it presents.

Our last push took me to the northern part of the crater, scrambling along a ridge right toward the main vents. The powerful, corrosive gases had bleached the upper rock into stark, dramatic colors, leaving the surface coated in a brilliant, snow-like mantle of white clay and sulfate deposits.

It was here that we got our first look at Lake Voui (two), which is now split into two separate bodies of water. The original large lake was bisected by the growth of the new volcanic cone that rose in the center. We could see active fumarolic activity concentrating near the southern shores of the lake.

The climb back out proved every bit as challenging as the descent, but I emerged exhilarated. As we made our way back across the caldera floor and up the steep wall to our camp, the fog began creeping in once more – our window of perfect conditions was over.